With the Desktop as a Canvas

By MATTHEW MIRAPAUL

The New York Times - December 18, 1997

No one would rest a Rolodex on a Rodin, so to regard the computer desktop as a work of art would seem to be as unlikely an activity as pasting a Post-It on a Picasso. The desktop is the computer's virtual workspace, a screen equipped with icons and windows that launch programs and yield data. It is normally judged on its functionality, not its appearance. Mostly, it is ignored.

Alexei Shulgin (pronounced SHOOL-gheen) wants you to take another look. In October, Shulgin launched Desktop Is, a Web-based art exhibition that prompts reconsideration of the visual importance of the desktop interface.

The site asks visitors to submit images of their own desktops. To date, almost 50 users have answered with screen shots taken from their PCs and Macs. A few are exactly that, a bland backdrop against which the others can be compared.

But the project also has inspired some of Shulgin's contributors to create clever and ornate responses to his challenge.

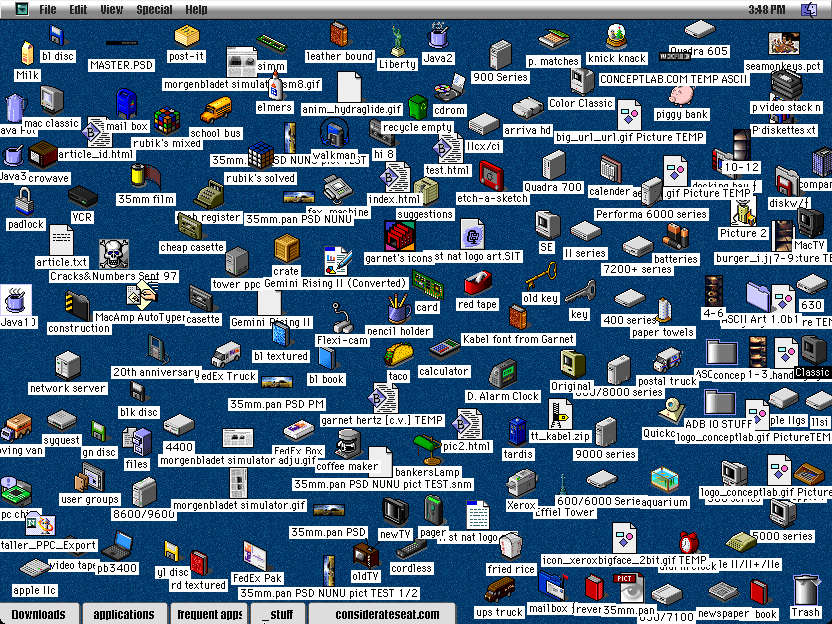

Garnet Hertz, a digital artist in Saskatchewan, Canada, constructed a cluttered collage of a couple hundred icons, ranging from the standard hardware and software symbols to tiny images of a taco, a piggy bank and a bottle of Elmer's glue.

A graphically simpler offering from Rachel Baker, a London-based Internet artist, makes a social comment. When read in sequence, the labels on her vertical stack of carefully arranged icons say, "bureaucracy does not allow disorganized desktops."

Among the most effective entries is a desktop by Natalie Bookchin titled "Male." The screen shows two open e-mail messages, but their texts are partially blocked by other windows that cannot be moved.

Provocative and ominous phrases such as "I find the idea that you would use my artwork as ransom quite painful" peek out, their meaning obscured by the interface. Bookchin, a visiting visual-arts lecturer at the University of California at San Diego, declined to reveal whether the messages were fiction.

Many of the desktops in the exhibit incorporate photographs, attempts to personalize the medium. Generally, these pictures look out of a place, much like a houseplant in an office cubicle that represents its owner's desperate effort to make a sterile environment feel homey.

The most playful variation on the photographic theme is Barbara Aselmeier's. Her screen boasts a dozen identical snapshots of a bearded, burly man. In each instance, he is naked but for a computer icon, a space-age fig leaf, covering his privates.

Along similar lines, it must be noted that two or three of the entries contain images that, while ambiguous, could easily be construed to be of a graphic sexual nature. They are even more shocking in their banal setting, so sensitive viewers must be cautioned.

Even without these elements, there is a voyeuristic aspect to the exhibit. If the desktop interface resists personalization (as the developers of Microsoft Bob, a friendly "front end" for Windows that bombed commercially, would surely attest), eyeing these samples can still resemble snooping through the neighbor's medicine chest.

Bookchin, who actually sent in two entries, explained: "The project was instantly appealing because, in a simple way, it sums up communication on the Net: people sitting in their own private spaces, communicating to remote private spaces. Each of our desktops becomes a continuously changing montage of private and public."

Shulgin, 34, is an artist and curator in Moscow, where he maintains the Easylife Web site. He also launched the Moscow WWW Art Centre three years ago and, with friends, he runs a two-month-old electronic mailing list devoted to art on the Internet.

While working on a project online, he stumbled across Kazuhiko Kiso's desktop, a serene screen with starry wallpaper (it is the first entry in the "Desktop Is" collection).

"It was so beautiful," Shulgin recalled. "I posted the image to the mailing list and I got a lot of response. I realized there was an interest, so I announced the exhibition. I was very surprised at how much response I have gotten."

In addition to building the list of entries, Shulgin also wrote a series of definitions for "Desktop Is," which include "your castle," "an extension of your organs," "your everyday torture and joy" and "a device for meditation."

Shulgin said he would accept submissions for six months from the Oct. 20 launch date. After that, he hopes to print out the entries and hang them on a gallery wall, although no site has been selected yet.

Refusing to take credit for "Desktop Is," Shulgin asserted: "All the borders between curators, artists and even audience are vanishing. It's not important any more who is who. Just the results are important."

"I see my role in this project not as a curator in the traditional role, but more like an administrator. I won't say it was my idea, because this idea was in the air and it was the result of some communication with other people. I just thought I would do it," he continued.

"For me, it was very exciting and interesting to see other people's desktops and feel like some community because the desktop is a very important thing. We spend so much time staring at it."

Surprisingly, none of Shulgin's contributors to date has used an art masterpiece as the basis of a desktop, perhaps an indirect acknowledgment that the interface has limited aesthetic potential.

But if the true value of a desktop does indeed reside in its functionality, the entries in Shulgin's exhibition cannot be judged. Because they are JPEGs and GIFs and Web pages, none of them work.

And that Stradivarius would make a splendid paper-clip dispenser, too.

|